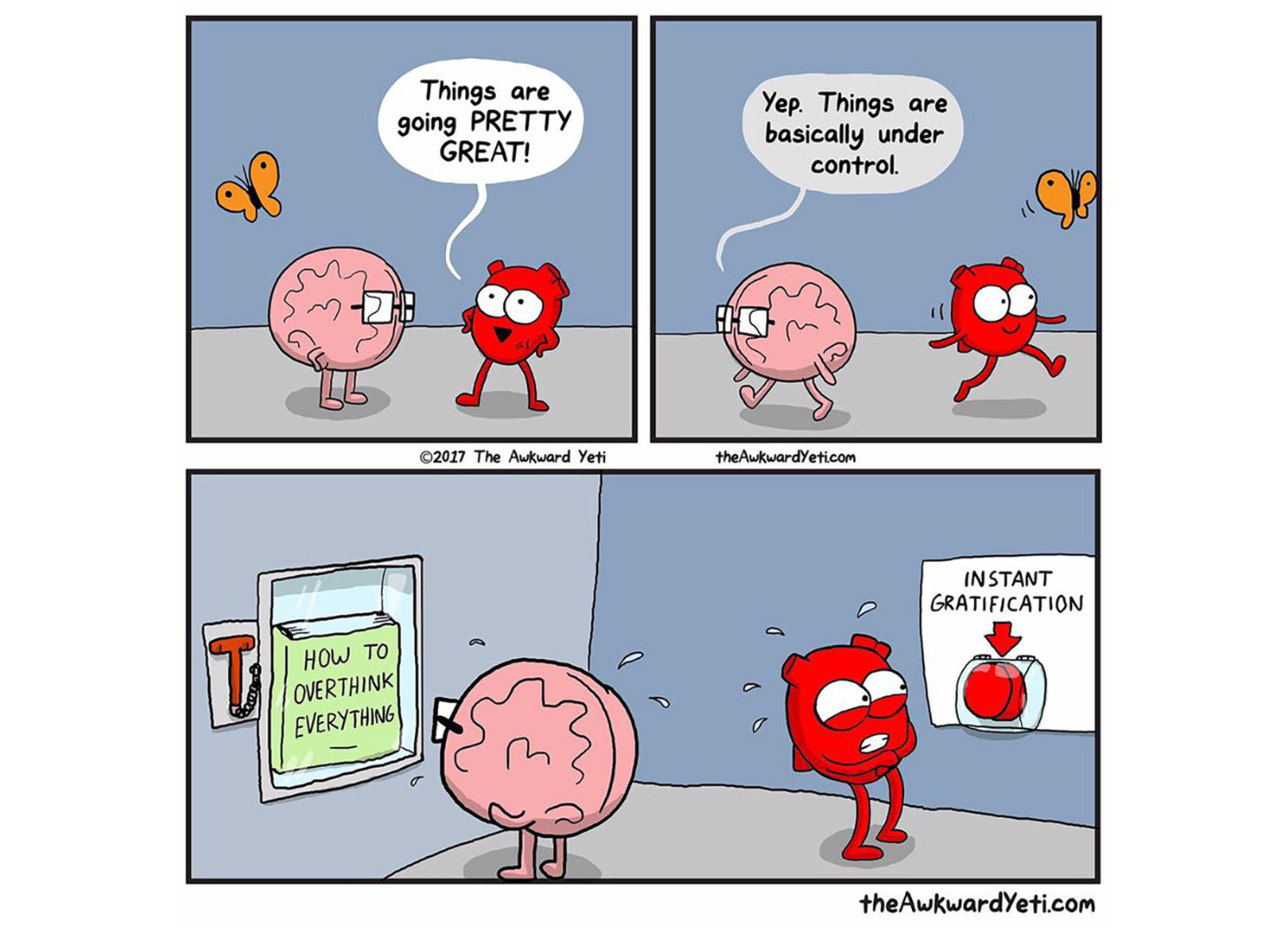

Just when everything seems under control, our brains have a way of reaching for the emergency manual titled How to Overthink Everything—as perfectly captured in the cartoon above.

Overthinking can sneak in exactly when we least expect it, turning moments of calm into spirals of doubt, indecision, and mental exhaustion. But psychology has a lot to say—and offer—when it comes to stopping this exhausting habit in its tracks.

Overthinking is when you repeatedly dwell on the same thoughts or worries, often to the point of feeling stuck. It’s not an official diagnosis, but chronic overthinking is closely linked to anxiety and depression and is commonly seen in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). People who overthink can become paralyzed by their worries, struggling to make decisions or take action. This mental habit can trap you in a loop of rumination, second-guessing, and negative self-talk, undermining your emotional well-being. Typical signs of overthinking include racing from one worry to the next, imagining worst-case scenarios, difficulty deciding (with lots of second-guessing), and constantly seeking reassurance.

Chronic overthinking can feel like your mind is racing against time, stuck in an endless loop of anxious thoughts. Research shows that excessive rumination and worry fuel stress and can worsen mental health over time. The good news is that psychology offers practical, evidence-based techniques to break out of this cycle. By learning to notice and manage your thought patterns, you can reclaim mental clarity and calm.

Breaking the Overthinking Cycle: General Strategies

Overthinking often feels productive—after all, you’re giving a lot of thought to your problems. But there’s a big difference between useful reflection and unproductive rumination. Psychologists note that rumination is not real problem-solving – it’s more like a mental treadmill, where you burn energy but don’t get anywhere. To break the cycle, it helps to take a step back and change how you respond to your thoughts. Here are some research-backed approaches for general overthinking:

Practice Mindfulness and Deep Breathing: Slowing down and focusing on the present can interrupt runaway thoughts. Deep, slow breathing directly calms the body and can reduce the physical stress of overthinking. Developing a regular mindfulness or meditation practice is an evidence-backed way to clear your mind of nervous chatter. Even a few minutes of mindful breathing or a short meditation each day can help you observe your thoughts without getting tangled in them. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence that inducing a mindful state reliably reduces rumination and negative emotions. Over time, mindfulness trains your brain to let thoughts pass without obsessing over them.

Challenge Negative Thoughts (Cognitive Restructuring): Overthinking is often driven by automatic negative thoughts – the critical or fearful voices in our head. In cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), people learn to notice these distortions and challenge their accuracy. For example, if your mind jumps to “Everything will go wrong”, pause and ask: What evidence do I have? Are there other possible outcomes? This technique, known as cognitive restructuring, has been shown to relieve pessimism, anxiety, and self-blame by replacing unhelpful thoughts with more balanced ones. Try writing down your worries and then brainstorming more realistic ways to view the situation. This process turns overthinking into active problem-solving. By recognizing that thoughts are mental events – not absolute truths – you can take away some of their power.

Ground Yourself in the Present: Overthinking pulls you into regrets about the past or fears about the future. To break free, engage your senses in the here-and-now. Simple grounding exercises (like noticing five things you see, hear, and feel around you) or mindful activities (like taking a walk and observing the sights and sounds) can snap you out of your head. Even enjoyable distractions help: doing something nice for someone else or a quick physical activity can shift your focus away from the whirlpool of thoughts. The key is to interrupt the overthinking process with a dose of real-world engagement, which gives your mind a chance to reset.

Accept Uncertainty – Don’t Overplay “What If” Scenarios: A major driver of overthinking is the discomfort with not knowing how things will turn out. We spin through “what if?” scenarios, trying to anticipate and control every outcome. Ironically, insisting on absolute certainty only fuels anxiety. Psychotherapists encourage practicing acceptance of uncertainty. Remind yourself that it’s okay not to have all the answers – life often doesn’t offer 100% guarantees. Rather than framing every decision as “right” vs “wrong,” see if you can view it simply as a choice among viable options. Any choice has potential upsides. By embracing a bit of uncertainty, you take pressure off your mind to ruminate endlessly.

Set Aside “Worry Time”: If anxious thoughts constantly intrude, give them a designated corner of your day. Scheduling a daily “worry time” (say 15 minutes each evening) is a technique used in CBT to contain rumination. Whenever worries pop up during the day, jot them down and tell yourself you’ll address them at the scheduled time. Many find that when “worry o’clock” arrives, the concerns feel less urgent or solvable. This method, often prescribed for GAD, helps you regain control by postponing repetitive worries. It trains the brain that you will deal with the concerns – just not all day long. Over time, this reduces the habit of constant overthinking.

Before diving into specific scenarios, remember that breaking the overthinking habit takes practice. At first, your mind will slip back into old patterns – that’s normal. Gently bring your focus to the present, challenge that negative thought, or engage in a task whenever you notice an overthinking spiral beginning. Small changes, repeated consistently, rewire your response to intrusive thoughts. Now, let’s explore how to apply these principles to particular types of overthinking, from anxious rumination to analysis paralysis and negative self-talk.

Rumination and Worry: Managing Anxiety-Related Overthinking

When you have anxiety, overthinking often takes the form of chronic worry or rumination – replaying fears, what-ifs, and worst-case scenarios in your mind. Psychologists call this repetitive negative thinking, and it’s like a mental hamster wheel that perpetuates anxiety. Research shows that worry and rumination are closely tied to anxiety disorders and depression. So how do we break the cycle of anxious overthinking?

One approach is to distinguish productive concern from unproductive rumination. Ask yourself: Am I actually solving a problem, or just dwelling on it? If there’s a concrete action you can take, do that (or make a plan to). But if you’re spinning on a problem with no new solutions, it’s likely rumination – and time to use a different strategy. Mindfulness techniques are especially useful here. Training in mindfulness has been shown to significantly reduce rumination in people prone to anxiety and depression. By focusing on your breathing or senses when worry takes over, you gently redirect your attention away from the fearful story your mind is telling. Even a brief mindful pause can cut off a cascade of “what if” thoughts.

Another evidence-based tactic for worry is practicing “detached mindfulness,” a concept from metacognitive therapy (MCT). Instead of engaging with each anxious thought, you learn to observe the thought and let it go – like watching clouds pass by. This approach addresses the thinking about thinking. For example, many chronic worriers hold positive beliefs about worry (“If I keep thinking about this, maybe I’ll prevent it”) or negative beliefs (“I can’t control my worrying – it will never stop”). MCT targets these beliefs. It teaches that trying to control or suppress thoughts often backfires, and that accepting thoughts as temporary events is more effective. In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that metacognitive therapy was highly effective at reducing anxiety and depression symptoms, even outperforming standard CBT in some trials. For an overthinker, the takeaway is: change your relationship to your thoughts. You don’t have to follow every worried thought down the rabbit hole – you can notice it, label it (“oh, that’s my anxiety talking”), and choose to redirect your attention.

Practical tips for anxious rumination include the earlier “worry time” technique, as well as redirecting to concrete action. For instance, if you’re stewing about something uncertain (say, an upcoming job interview), it might help to do a specific task related to it (like preparing answers or talking to a friend for support). If you’ve done what you realistically can, then give yourself permission to put the topic aside. Engage in an activity that occupies your mind – exercise, cooking, a good book or movie – essentially, change the channel. Research suggests that even brief distractions can reduce acute rumination and ease anxiety. Over time, consistently interrupting rumination with either mindful acceptance or constructive problem-solving will weaken the hold that worry has on you.

Analysis Paralysis: Making Decisions Without Overthinking

Do you ever struggle to make a decision because you’re over-analyzing every option? If so, you’ve faced analysis paralysis – a form of overthinking where the fear of making the “wrong” choice leaves you frozen. This often happens with perfectionists or maximizers (people who feel they must choose the absolute best option). In aiming for perfection, you end up stuck and anxious, endlessly weighing pros and cons.

Decision paralysis can also stem from anxiety. You might catastrophize outcomes (“If I choose wrong, it’ll be a disaster”) or doubt your ability, leading you to seek constant reassurance or more and more information. Ironically, too much information can overload you and immobilize the decision process. If you find yourself researching trivial choices for hours or postponing important decisions repeatedly, you may be caught in this overthinking trap.

Over-analyzing a decision can leave you perched anxiously on a question mark, no closer to an answer. To break out of analysis paralysis, practice making decisions under gentle constraints. One strategy is to start with small, low-stakes choices and give yourself a strict time limit. For example, when picking a show to watch or a restaurant to order from, limit yourself to 5 minutes of deliberation and then decide. By doing this regularly, you train your brain to tolerate making a choice without exhaustive analysis. It builds confidence that “good enough” decisions can turn out fine. In fact, research on decision-making styles finds that “satisficers” (those who settle for a good-enough option) tend to be happier with their choices than perfectionist “maximizers,” who are prone to regret.

For bigger decisions, try these tips:

Set a Deadline and Prioritize: Give yourself a reasonable timeframe to decide, and focus on the few factors that matter most to you. Recognize that waiting for absolute certainty is unrealistic – at some point, you have to choose and see what happens. Setting a deadline can prevent infinite procrastination.

Limit Information Overload: Do enough research to be informed, but beware of falling down the rabbit hole of reviews, opinions, and endless options. Identify 2–3 reliable sources or a handful of options, then stop. Give yourself permission to trust your knowledge and gut instinct once you’ve covered the basics.

Reframe the Decision: Instead of treating it as a right vs. wrong dilemma, remind yourself that in many cases there may be multiple acceptable outcomes. It’s rarely true that only one choice leads to happiness and all others spell doom. Often, we create a false dichotomy of a “perfect” versus “terrible” choice, when reality might be several good choices. Adopting this mindset takes pressure off. Try telling yourself: “Both Option A and Option B could work out well – they’re just different.” This makes it easier to pick one and move forward.

Take Breaks to Reset: When you notice you’re stuck in a decision loop – feeling increasingly anxious and less clear the more you think – step away if possible. Decision fatigue is real: the more we obsess, the more mentally exhausted we become, which further impairs decision-making. Take a short walk, do a few minutes of deep breathing or stretching, or switch to a simple task to give your mind a break. Coming back with a fresher mind can lend perspective. You might realize that whichever choice you make, you’ll adapt and be okay.

By using these techniques, you can unclog the decision-making process. The goal is to move from analysis to action, even if that action is not perfect. Over time, you build trust in your ability to decide, which reduces the anxiety that fuels overthinking. And remember, not deciding is also a decision – it often leads to missed opportunities or default outcomes. So it’s usually better to make a thoughtful choice, learn from it, and keep progressing, than to be stuck in place over-analyzing.

Negative Self-Talk: Overcoming the Inner Critic

Overthinking isn’t just about decisions or future worries – a lot of it happens internally as negative self-talk. This is the running commentary in your mind that might say “I’m not good enough,” “I always mess up,” or “What’s wrong with me?” when something goes awry. An overly harsh inner critic can magnify stress and anxiety, turning every setback into proof of personal failure. Psychologists find that high levels of self-criticism and frequent negative self-talk often accompany more serious issues like depression, anxiety, and even eating disorders. In other words, how you talk to yourself matters for your mental health.

The first step is to recognize the negative tape playing in your head. Pay attention to your self-talk, especially in moments of stress. Are your thoughts overly critical or catastrophic? Common cognitive distortions include blaming yourself for things out of your control, filtering out positives, or expecting the worst. Once you catch these thoughts, you can apply techniques from CBT to change them. In fact, CBT is built to help with negative self-talk: it teaches you to examine the evidence for your thoughts, test out alternative interpretations, and develop a kinder inner dialogue. For example, if your inner critic says “I can’t do anything right,” pause and challenge that. Is that literally true? Probably not – you can likely list some things you’ve done well. By talking back to the inner critic with facts and a more balanced view, you diminish its influence.

Another powerful strategy is to practice self-compassion. Instead of berating yourself for mistakes, treat yourself as you would a good friend – with understanding and encouragement. Research is increasingly showing that self-compassion is a potent antidote to negative self-talk. In one review, people who learned self-compassion techniques experienced significant benefits to their well-being. Self-compassion doesn’t mean letting yourself off the hook for responsibilities; it means not adding unnecessary self-blame and shame on top of life’s challenges. The next time you catch yourself thinking, “I’m such an idiot for overthinking this,” try reframing it: “I’m human, and I’m doing my best. Everyone overthinks sometimes. I can learn from this and move on.” This kind of gentler inner voice can actually motivate you more effectively than criticism – studies show that people who practice self-compassion tend to have greater resilience and motivation because they aren’t dragged down by fear of failure.

In practice, overcoming negative self-talk might involve journaling exercises (writing down a negative thought and then writing a more compassionate response), using affirmations that you truly believe in (“I have handled challenges before, I can handle this too”), or even brief mindfulness meditation focused on self-kindness. Mindfulness is useful here as well, because it helps you observe thoughts without immediately buying into them. Over time, you can cultivate an “inner coach” to counter the inner critic – a voice that is realistic but forgiving, encouraging you to improve without tearing you down.

Finally, remember that thoughts are not facts. Just because you think “I’m a failure” doesn’t make it true – it’s a mental event influenced by mood and habit. By consistently disputing negative thoughts and treating yourself with kindness, you’ll find that the volume of the inner critic turns down. With a quieter inner critic, your mind has more space for productive, creative, and positive thoughts, reducing the overall tendency to overthink in destructive ways.

New Tools and When to Seek Help

Thanks to psychological research, we have a toolkit of strategies – mindfulness, CBT techniques, self-compassion, and more – that can significantly reduce overthinking. In addition, emerging innovations are making these tools more accessible. For example, mobile apps and digital programs are being developed to help people manage worry and rumination in their daily lives. A recent randomized trial found that a self-help app targeting repetitive negative thinking led to significant reductions in worry and rumination among young adults, along with improvements in anxiety and depression, compared to a control group. The fact that benefits were seen with an unguided app is promising – it suggests that technology can provide on-demand help to break thought loops.

Similarly, researchers have created gamified apps that turn the fight against rumination into a sort of game. One such app uses mini-games to disrupt depressive rumination and encourage more flexible thinking. In an 8-week study, participants using the app showed faster improvement in depressive symptoms than those who didn’t, and the gains lasted at least a month after the study. These innovations are still being refined, but they point to a future where proven techniques (like redirecting thoughts or challenging beliefs) can be delivered in engaging, user-friendly ways right on your smartphone. For an overthinker, that could mean help is available exactly when you need it – the moment you notice yourself spiraling, you might play a 5-minute game or follow a guided exercise that snaps you out of it.

While self-help strategies and apps can be very effective, there are times when professional help may be the best course. If overthinking is causing you significant distress, fueling anxiety or depression, or interfering with your daily life, consider reaching out to a mental health professional. Therapists can offer personalized techniques and support. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, for instance, has a strong track record: a recent meta-analysis confirmed that CBT significantly reduces repetitive negative thinking like worry and rumination. Newer therapies like metacognitive therapy (discussed earlier) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) also specifically target the rumination process. Even a few sessions can equip you with tailored tools to manage overthinking. In some cases, therapy combined with medication for underlying anxiety or depression can provide relief and restore balance.

Takeaway: Overthinking is a common challenge, but you are not powerless against it. By applying these science-backed strategies, you can catch yourself in the act of overthinking and gently steer your mind toward a healthier track. Whether it’s through a daily mindfulness habit, a CBT worksheet, a supportive friend, or a new app on your phone, you can train your brain to stress less and live more. Remember, the goal is progress, not perfection – every time you refocus your thoughts or choose action over rumination, you’re building mental habits that make it easier to stop overthinking and find peace of mind.

Have you tried any of these strategies to stop overthinking?

I’d love to hear what worked for you—or if you have your own go-to tips or mental hacks for calming a busy mind. Feel free to share your thoughts, experiences, or questions.

Stay in the know! The All About Psychology newsletter is your go-to source for all things psychology. Subscribe today and instantly receive my bestselling Psychology Student Guide right in your inbox.

Upgrade to a paid subscription and also get the eBook version of my latest book Psychology Q & A: Great Answers to Fascinating Psychology Questions, as well as regular psychology book giveaways and other exclusive benefits. As a paid subscriber, you will also be:

Ensuring that psychology students and educators continue to have completely free access to the most important and influential journal articles ever published in the history of psychology.

Ensuring that psychology students and educators continue to hear from world renowned psychologists and experts.

Ensuring that free quality content and resources for psychology students and educators continue to be created on a regular basis.

Providing free, high-quality information and resources since 2008, All-About-Psychology.Com receives well over a million visits a year and has attracted over a million followers across its social media channels.

If you are looking to supercharge your brand awareness and reach, or promote your course, book, podcast, product or service; I can help.

Visit the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.

For more psychology information and resources, visit All-About-Psychology.Com and connect with me via the All About Psychology social media channels:

LinkedIn Psychology Students Group