Like many people of my generation, my first real sense of what it meant to be “cool” came from television. As a kid, I was mesmerized by The Fonz in Happy Days - with his leather jacket, slicked-back hair, and signature “Ayyyy” - he didn’t just walk into a room, he owned it. Later, it was Crockett and Tubbs from Miami Vice who redefined cool for me: stylish, emotionally reserved, and always in control, even when things got intense. They weren’t just characters, they were cultural icons who embodied something magnetic, elusive, and universally admired.

But what exactly is that something? What makes cool people cool?

It’s a question that’s fascinated pop culture commentators, marketers, and psychologists alike, and now, thanks to a landmark global study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, we finally have a scientifically grounded answer. Drawing on data from nearly 6,000 participants across 13 countries, researchers Todd Pezzuti, Caleb Warren, and Jinjie Chen set out to identify the psychological traits that define coolness - and whether those traits hold up across cultural boundaries.

In this article, we’ll explore their findings in detail, before stepping back to trace the fascinating origins of “cool” as a cultural concept; from its roots in jazz and emotional restraint to its global spread through film, fashion, and social media. Finally, you’ll find a set of reflection questions designed to help you dig deeper into your own perceptions of coolness, ideal for personal insight, discussion, or student project work.

Let’s begin with the science.

What Makes Cool People Cool? A Global Psychology Study Explains

What does it truly mean to be a "cool person"? We throw the word around easily; about a friend’s style, a celebrity’s attitude, or a stranger’s confident silence, but few of us could define it precisely. And yet, somehow, we just know it when we see it. The idea of cool has long hovered between pop culture and personal aspiration. But only recently has psychological science stepped in to ask: is coolness a real, measurable phenomenon? And if so, what traits define cool people and are they the same the world over?

A recent study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General tackles these very questions. Led by Todd Pezzuti, Caleb Warren, and Jinjie Chen, this large-scale research project set out to investigate the psychology of coolness. What emerged is perhaps the clearest and most compelling scientific account yet of who cool people are and why they matter.

Moving Beyond the Stereotype

For decades, coolness has been a staple of youth culture, branding, rebellion, and social commentary. From James Dean’s brooding quiet to Beyoncé’s effortless magnetism, cool has been aspirational and elusive. But Pezzuti and his colleagues weren’t interested in celebrity cool or stylistic trends. Instead, they focused on the psychological attributes that make ordinary individuals appear cool to others.

The study involved nearly 6,000 participants across 13 countries, including the U.S., China, India, Germany, Mexico, and South Africa. In each location, respondents were asked to think of a non-famous person they considered to be cool - or not cool - and rate that person on a wide range of traits and values. This design allowed the researchers to sidestep fleeting pop culture definitions and get closer to what people intuitively mean by “cool” across diverse societies.

Cool Is Not the Same as Good

A central innovation of the study was its distinction between “cool” and “good.” The authors recognized that while cool people are often seen positively, not all good people are cool and vice versa. A kind, dependable grandmother might be deeply good, but she’s unlikely to be described as cool. So what sets coolness apart?

The answer lies in a specific psychological profile.

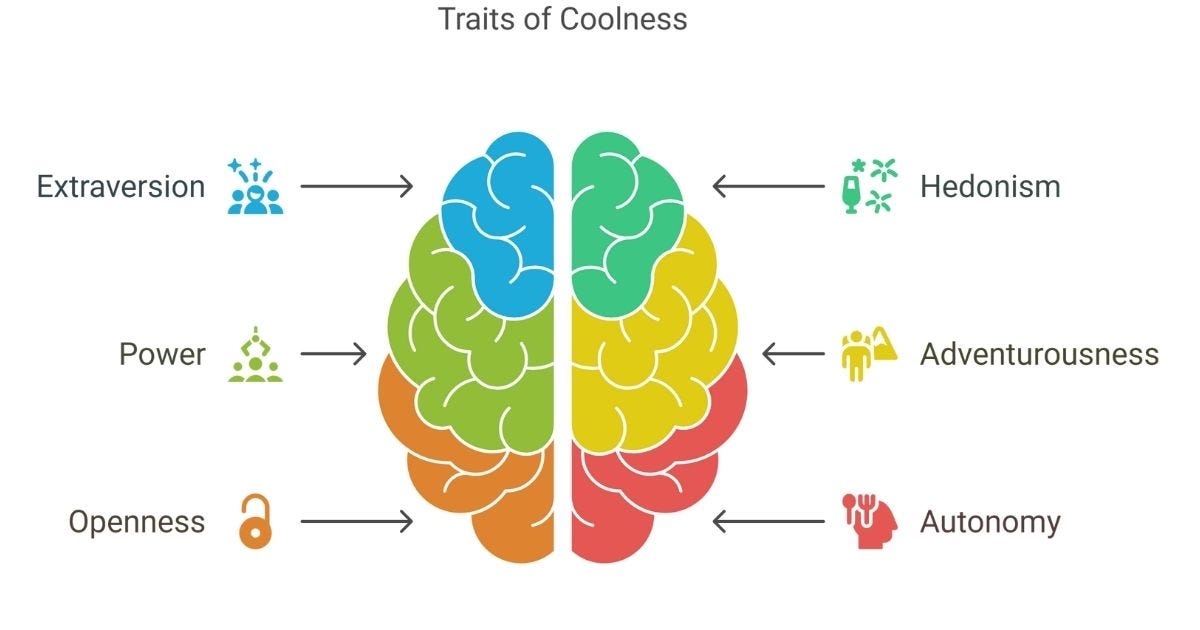

The researchers identified six traits that consistently and significantly distinguish cool people from everyone else:

1. Extraversion – They’re outgoing, energetic, and socially confident.

2. Hedonism – They seek pleasure and enjoyment in life.

3. Power – They are perceived as influential or having a strong presence.

4. Adventurousness – They embrace novelty, excitement, and risk.

5. Openness – They’re curious, imaginative, and open to new ideas.

6. Autonomy – They think and act independently, not bound by convention.

These traits form the psychological backbone of what people around the world intuitively perceive as “cool.”

By contrast, people described as “good” tended to be more conforming, traditional, secure, warm, agreeable, conscientious, and calm, qualities that support harmony, reliability, and morality, but don’t necessarily inspire admiration in the same edgy or aspirational way.

It would appear then, that coolness is distinct from goodness. It’s more socially magnetic than morally upright, more admired than trusted, more status-oriented than nurturing.

Coolness Is a Cross-Cultural Constant

One of the most remarkable findings of the study is the cross-cultural stability of the coolness profile. Despite cultural differences in values and norms, the same six traits - extraversion, hedonism, power, adventurousness, openness, and autonomy - were strongly associated with coolness in every single country surveyed.

This is particularly striking because many of these traits (such as autonomy or hedonism) might seem to contradict the values of more collectivist or traditional societies. And yet, people across cultures consistently identified these traits as cool, even if they didn’t always approve of them.

This suggests that coolness may serve a universal social function. According to the authors, cool people may operate as cultural pioneers - testing limits, challenging norms, and influencing social hierarchies. Their charisma and confidence allow them to defy expectations and still earn admiration. In this way, coolness might help societies adapt and evolve by rewarding a certain kind of norm-bending behavior.

Why This Matters

At first glance, the study of coolness might seem trivial or superficial. But dig deeper, and you’ll find something profound. The desire to be seen as cool isn’t just a teenage phase, it’s a deeply human yearning to be admired, influential, and unique, yet still socially accepted.

Coolness confers status without authority, influence without coercion, and respect without conformity. It’s a form of cultural capital that shapes how people present themselves, whom they emulate, and what behaviors they value.

Understanding what makes someone cool gives us insight into how we construct identity, aspiration, and belonging. It also helps us appreciate the psychological balancing act at play: cool people are different but not too different. They stand out, but they’re not isolated. They are nonconformists who remain socially desirable.

So, what can you take from this research?

You may not be able to fake cool, but you can understand it. Coolness, as this study shows, is not about being aloof or trend-obsessed. It’s about projecting confidence, curiosity, independence, and charisma - qualities that make people not only stand out, but inspire.

Whether you're an educator, marketer, leader, or simply someone intrigued by human behavior, understanding the science of cool people opens a window into how admiration is earned, how cultures converge, and how we negotiate our place in the social world.

Coolness, it turns out, is not just skin-deep. It's a signal; one that speaks volumes about our values, our psychology, and our universal desire to be seen.

The Origins of Cool: A Cultural History

Now that we understand what makes cool people cool from a psychological perspective, it’s worth stepping back to explore where this powerful concept came from and how the meaning of “cool” evolved into a global social phenomenon.

The idea of being “cool” might feel modern - closely tied to Instagram influencers, trendsetting celebrities, or effortlessly stylish peers - but its roots run much deeper, weaving through centuries of cultural, social, and psychological evolution.

From Temperature to Temperament

The word cool has existed in English since at least the 8th century, originally describing temperature i.e., something “moderately cold.” By the 14th century, cool also began to denote emotional restraint: someone who remained calm, composed, or unflustered. This early link between emotional regulation and the term cool laid the groundwork for the psychological meanings that would emerge centuries later.

Coolness and Black American Culture

The concept of cool as a social identity - a persona or attitude that signals confidence, nonchalance, and defiance - began to crystallize in African American communities in the early 20th century, particularly in the jazz scene.

In the face of systemic racism and social exclusion, Black musicians, artists, and thinkers cultivated a form of emotional self-possession and dignified distance that became a form of resistance. By staying “cool” under pressure - refusing to let anger, fear, or vulnerability show - individuals could assert autonomy and dignity in a society that denied them both. In this way, cool became more than an attitude. It was a coded form of psychological self-protection and cultural power.

Jazz legends like Lester Young and Miles Davis epitomized this idea in the 1940s and ’50s, helping shape a stylized, emotionally controlled form of creative expression that influenced everything from fashion to film. Davis, famously enigmatic and aloof, once said, “When you’re creating your own shit, man, even the sky ain’t the limit.” He didn’t just perform music - he performed cool.

Cool Goes Mainstream

In the postwar period, the meaning of cool expanded beyond jazz clubs and into popular youth culture. Films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and The Wild One (1953) portrayed rebellious antiheroes - like James Dean and Marlon Brando - who embodied cool’s emotional restraint, outsider status, and confident independence.

By the 1960s and ’70s, cool had become a countercultural badge, associated with nonconformity, artistic expression, sexual liberation, and social rebellion. Coolness wasn’t just about being stylish, it was about challenging the system while staying effortlessly unbothered.

This era also cemented the idea that cool is socially constructed: it’s not something you are, but something others perceive you to be. If people agree you’re cool, you are. If they don’t, you're not.

The Democratization of Cool

Fast-forward to the digital age, and coolness has become even more performative and public. From MySpace to TikTok, people now curate their lives as a form of digital cool; crafting images, aesthetics, and identities to win likes, follows, and social status.

And yet, the core qualities remain surprisingly stable: autonomy, charisma, novelty, and edge. What Pezzuti and colleagues found in their 13-nation study echoes what has been centuries in the making - coolness is a universally recognizable signal of social distinction.

Reflection Questions: What Makes Cool People Cool?

If you would like to explore the psychology of coolness in greater depth, the following reflection questions are designed to encourage personal insight, classroom discussion and inspiration for psychology project work. I’d love to hear your thoughts, so feel free to share your reflections via the Leave a comment button below!

Personal Insight

When you think of someone you consider “cool,” what traits or behaviors come to mind? How closely do these align with the six traits identified in the study: extraversion, hedonism, power, adventurousness, openness, and autonomy?

Do you see a difference between someone who is cool and someone who is good? Can you think of examples from your life or public figures who fall into each category?

Which of the six “cool traits” do you most identify with and which do you struggle with? What does that tell you about how you present yourself and how others might perceive you?

Have you ever tried to appear cool? What strategies did you use, and did they work, or backfire?

Cultural Reflection

In your culture or community, who is typically considered cool? Are the same traits admired across different generations, regions, or subcultures?

How has your understanding of coolness been shaped by media, music, or fashion? Think about how movies, social media, or celebrities have influenced your perception of what “cool” looks like.

Does emotional restraint still signify coolness in your environment? Or do you see a shift toward expressiveness and vulnerability being admired instead?

How do you think coolness operates in digital spaces today? Does social media reward the same traits identified in the study, or does it encourage a different kind of performance?

Psychological Depth

Why do you think people are so drawn to being seen as cool? What psychological needs might this fulfill - status, identity, autonomy, belonging?

How might coolness serve as a social tool for shaping norms or challenging authority? Can you think of historical or contemporary examples where coolness has driven cultural or social change?

What’s the risk of chasing coolness? When might the desire to be perceived as cool come at the expense of being authentic, kind, or emotionally open?

Integrative Challenge

If you were to redefine “cool” for the next generation, what traits would you include and why? How might your definition reflect your values, culture, or hopes for the future?

Maybe the coolest people are the ones who don't care about being cool. (Steve Carell)

Stay in the know! The All About Psychology newsletter is your go-to source for all things psychology. Subscribe today and instantly receive my bestselling Psychology Student Guide right in your inbox.

Upgrade to a paid subscription and also get the eBook version of my latest book Psychology Q & A: Great Answers to Fascinating Psychology Questions. As a paid subscriber, your support for the All About Psychology platform will help ensure that:

Psychology students and educators continue to have completely free access to the most important and influential journal articles ever published in the history of psychology.

Psychology students and educators continue to hear from world renowned psychologists and experts.

Free quality content and resources for psychology students and educators will continue to be created on a regular basis.

🚀 Want to get your brand, book, course, newsletter or podcast in front of a highly engaged psychology audience?

All-About-Psychology.com now offers advertising and sponsorship opportunities across one of the web’s most trusted psychology platforms - visited over 1.2 million times a year and supported by over 1 million social media followers.

Whether you're an author, educator, startup, or organization in the psychology, mental health, or self-help space - this is your chance to stand out.

🎯 Exclusive placement

🔗 High-authority backlink

👀 A niche audience that actually cares

Learn more and explore advertising and sponsorship options here:

👉 www.all-about-psychology.com/psychology-advertising.html

Visit the All About Psychology Amazon Store to check out an awesome collection of psychology books, gifts and T-shirts.

🌐 Explore Comprehensive Psychology Content - For Free!

Looking for clear, credible, and comprehensive psychology information?

Visit All-About-Psychology.com - your go-to hub for resources, articles, and expert insights across every major area of psychology.

And don’t forget to connect with the All About Psychology community across social media:

🔹 Facebook – Join over 800,000 psychology enthusiasts

🔹 LinkedIn – Connect with professionals and academics

🔹 LinkedIn Psychology Students Group – A dedicated space for students to share and learn (over 180,000 members)

🔹 Instagram – Visual insights, quotes, and key concepts

🔹 Pinterest – Curated boards on topics across the field

🔹 Bluesky – Latest platform for psychological conversation

🔹 YouTube – Watch engaging, science-backed videos that bring psychology to life

Whether you’re learning, teaching, researching, or simply curious - you’re always welcome in the All About Psychology community.

I’m definitely not cool but I think I may be good.

What a great overview of the positive characteristics of "Cool". I can't help but wonder about the maladaptive elements. Perhaps the Dark Triad factors in with those 6 elements you've shown us?